Identifying Skill Issues

Video Games; or, how we can learn to see the world in new ways

“Video games are bad for you? That’s what they said about rock and roll”

– Shigeru Miyamoto the inventor of Mario, Donkey Kong, and The Legend of Zelda

Humans love to play, and we have been creating games to help us play for a very long time. We have found dice at archaeological sites from well before 5000 BC, and the oldest board game we know of comes from an Egyptian burial site dating to 3500 BC. Over the last 50 years, though, a new medium for game play has come to dominate our societies: video games.

In June of 1972, video gaming escaped from the confines of toy projects in research labs and entered the mainstream when Nolan Bushnell created Atari and they put out their first product: pong, the first arcade game. Almost immediately video games became a huge industry. By 1982, the video game market, driven mostly by arcade games, had more revenue than movies. In 2022, video games brought in more than $180 billion globally—more than any other form of entertainment.

Yet this rise of video games has not been without concern.

In the US, there have been repeated waves of worry about video games. Pinball machines, a proto-video game, were termed 'insidious nickel stealers' and banned in NY in 1942. The 1999 Columbine High School shooting produced a moral panic over whether violent video games cause aggression. Today, as video games have become ubiquitous, they have been implicated in anxiety, depression, ADHD and more - especially among kids.

In China, the worries are even more serious; recently one state news outlet even called them “spiritual opium.”1, a loaded phrase given Chinese history. Concerns range from worries that video games cause myopia to fears that they will divert attention from more productive work, and even decrease masculinity. As a result, the government has banned gamers under 18 from playing from playing for more than one hour on Fridays, weekends and holidays.

At the same time, video games have been described as a promising platform for skill acquisition, and in particular for teaching kids. Evangelists say that games are perfectly suited for 'brain training', improving cognitive abilities, and teaching new subjects, pointing to gamers such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg for proof that games correlate with genius.

So, what is it? Do video games offer new avenues for skill acquisition and cognitive development, are they merely a fun distraction, or even a risk to our mental health and social order? Given the growing time and money we spend on them, we should probably care very much2.

Video games, like all avenues for play, are a powerful way to learn rudimentary skills. Video game environments are also uniquely suited to developing an increasing sense of agency and a flexibility in taking on new roles in the real world. This is especially true for children and for people just starting to develop new faculties. But, they also bring risks: video games can stunt skill development just as easily as start it, and addiction is real and damaging. Nevertheless, we should not fear video games, and instead should treat them with respect and give them their due place in society.

The Prospects of Gamification

"I never said bad games are good for learning" – Jim Gee

Interest in the relationship between video games and skill acquisition began quite early in the life of the medium. It quickly became clear that dedicated gamers would devote a huge number of hours to play: serious gamers will routinely spend more than 10,000 hours on their favourite game.

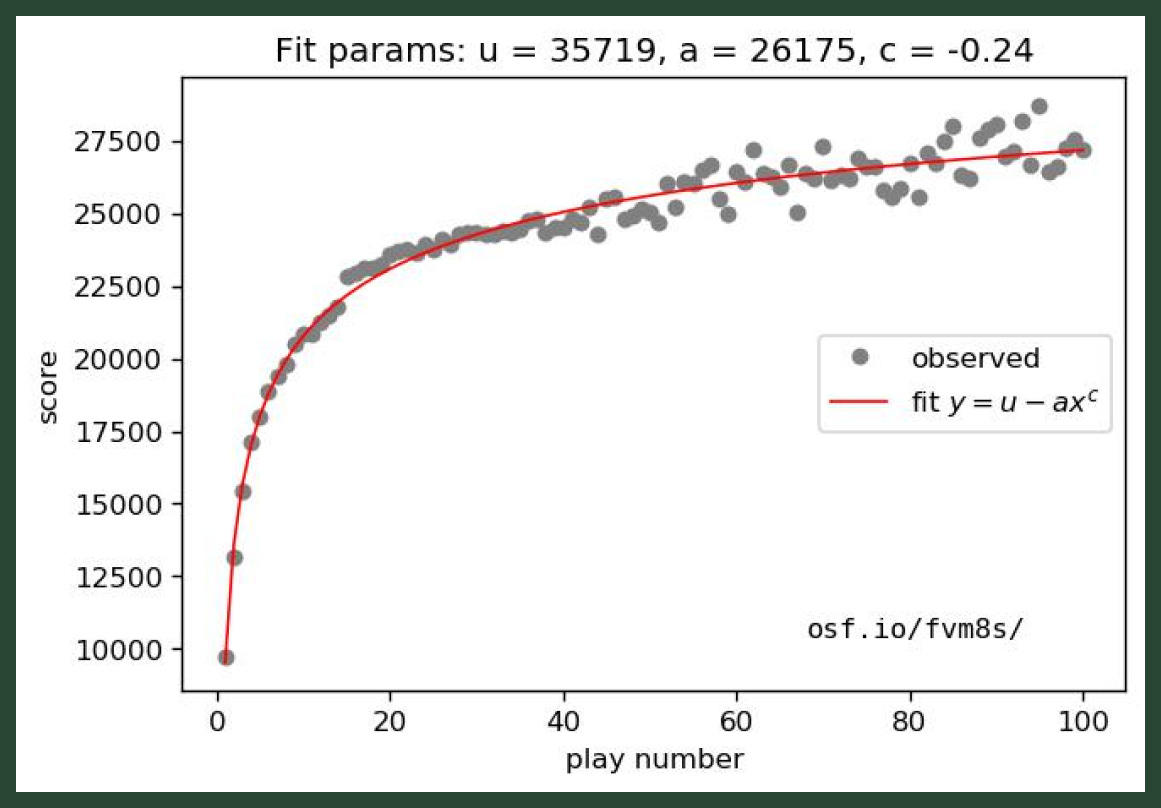

It was also clear early on that gamers' skill levels improve over time. Empirically, users have nearly perfect classical learning curves: the more they play, the better they get, with diminishing returns.

This high level of engagement and the unambiguous learning curves are closely related. Both exist because video games are engineered from the ground up to create a sense of “competence satisfaction": a feeling of "leveling-up, continual advancement without a clear plateau, a clarity of goals, [and] granular and cumulative feedback"3.

Video games do this in two ways. First, they create a well-defined landscape of things that matter to the gamer. This might be through showing quantitative measures of health or ability, using arrows to point to relevant objects like treasure chests, or providing feedback when you strike an enemy. Second, they match the player's abilities to this landscape. There are varying degrees of difficulty, but you can be sure you have the tools necessary to win.

This feeling of competence combines with a sense of autonomy that comes from being able to make real choices within the game. This combination of competence, satisfaction and autonomy means the video game environment is engineered from the ground up to feel like a place of mastery: "Unlike most real-world domains, such as work and school, virtual environments can offer intrinsic need satisfactions with immediacy, consistency, and density".4

So video games are highly motivating, but it's not clear that this makes them useful for building competencies outside the game world.

At a macro scale, video games have been hypothesized to improve hand-eye coordination, strategic thinking, and even intelligence more generally. However, in almost all domains, there is no concrete evidence for these claims.

The vast majority of empirical studies have serious methodological problems. Tests of specific effects from gaming usually are conducted on a limited number of users, test a complex intervention that is hard to repeat, and draw conclusions from small effect sizes.

When testing at the population level, studies will compare groups that play video games or don't and try to draw conclusions, but they usually give little attention to potential confounding factors. For example, one influential study claims that video games significantly improve processing speed, deductive reasoning, and mathematical intelligence in Pakistani children. But the study looks at these self-described gamers vs. non-gamers without considering, for example, whether the gamers are from higher-income families — which would make sense, given that video games require both money and leisure time. If that were the case, you would then have to ask whether these differences were driven by the better nutrition and schooling available to the wealthy, amongst other things.

Despite these issues, there does seem to be some consensus that action games may marginally help with perceptual attention skills, and some puzzle games like Tetris can help with particular tasks, such as spatial rotation. Still, it hasn't been shown that this translates more broadly. In the case of brain training and general cognitive improvement, there is a "lack of consistent evidence that long-term exposure to brain training ... improves performance on non-game measures of executive function"5.

In a more targeted way, video games have been considered a potential way to improve education and teach technical subjects such as maths, science, and languages. Some approaches here are promising, but none have yet been found to be a silver bullet in their domains. When they do seem to work, the most consistent reason given is that they lead to more attention to the material over a longer period of time. As one researcher describes it, "The use of games and gamification is therefore most essentially a motivational intervention—a strategy to facilitate sustained engagement."6.

Is this strategy a good one when it comes to skill acquisition? To answer this question, we need to consider Duolingo and the gamification of language.

The Case of Duolingo

“To have another language is to possess a second soul” – Charlemagne

When Duolingo was released in 2012, I was in university starting to learn Chinese, and the app made a splash in my circles of the internet. It was endorsed by Tim Ferris, and one paper claimed that the app would teach the equivalent of a first college semester in Spanish in ~30 hours—a compelling proposition for a 19-year-old in their second college semester of language learning. Since then, Duolingo has become incredibly popular.

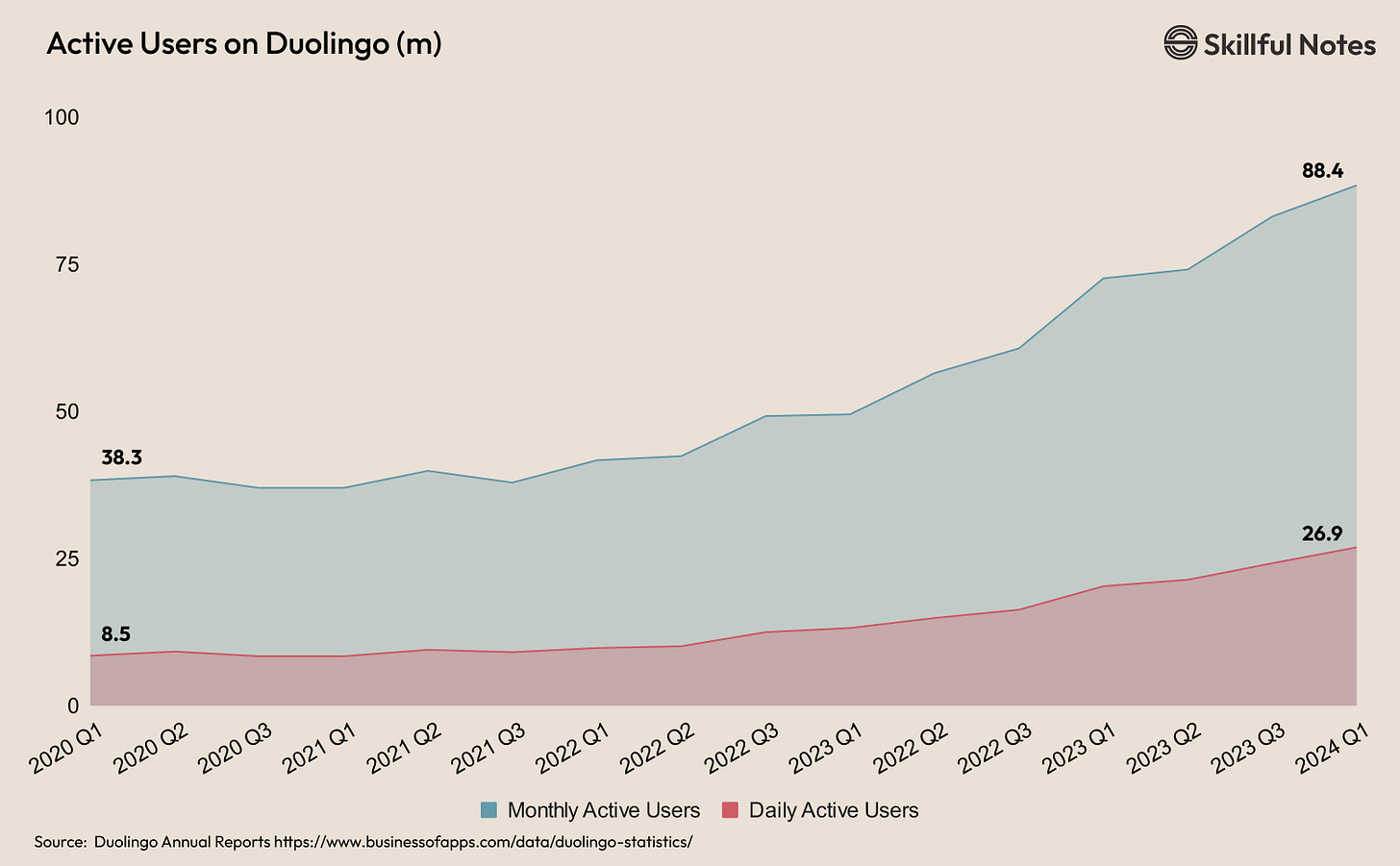

The core of Duolingo's appeal is that it takes the gamification of language learning to the highest possible level. Badges, levels, points, reminders, and social aspects combine to create a hyper-compelling experience. A multitude of memes attest to the almost-painful feeling that comes with breaking a learning streak, and Duolingo appears to be getting even better at this: in the last four years, the ratio of daily active users to monthly active users has grown from 22 percent to 30 percent.

This popularity has spurred research into the app’s effectiveness, but as with other research into skill acquisition, the answer here is unclear. Some argue that it works incredibly well, while others see it as a tool with limited use. Which way you see it seems to depend on what you think Duolingo should be doing.

One class of studies, such as the paper cited above, measure the app by vocabulary and grammar principles learned. These usually find that it "can promote acquiring two languages"7 and is "easy to use"8.

The other approach asks whether Duolingo actually helps people speak another language so they can use it in their life. From this angle, the results are less impressive. Researchers have found that the app is not based on "communicative competence"9 and that it cannot provide “adequate help for advanced learners” or help in "spontaneous speech production".

This is exactly the dynamic that language learners describe. When you are starting out on a language, Duolingo is a great tool for rapidly getting up to speed on basic vocabulary and grammar, and for seeing a lot of examples. However, for reaching real fluency, it quickly outlives its usefulness. It’s easy to develop a streak because of the gamification, but that streak soon becomes counterproductive to the real aim of learning a language.

This is the issue on which skill acquisition and video games ultimately turns.

A video game constructs a specific realm for action, with clear goals, abilities, obstacles, and feedback. This realm is one with intense experiences of competence satisfaction, but it also defines the limits of the kind of competencies you can develop.

This is all fine and good so long as you are just getting started or need a rudimentary introduction to something and there is always room for some amount of skill transfer10. However, the fantasy world that the video game creates is deeply compelling even after this initial period. If you continue to play past the point of gaining an introduction to the skill, you risk not only wasting your time but even warping your ability to really learn.

Agency, Addiction, and Play

"The value of games is to be found in the flowering possibilities of the art of agency"

– C. Thi Nguyen

“Play is the work of childhood"

– Jean Piaget

In his work Games: Agency as Art, C. Thi. Nguyen frames this fact of games—that they create an artificial world for developing competence—by arguing that they are in fact a kind of aesthetic product. In the same way that painting is the art of creating visualization, music is the art of creating sounds, and so forth, games are the art of creating a particular type of agency.

A game tells us to take up a particular goal. It designates abilities for us to use in pursuing that goal. It packages all that up with a set of obstacles, crafted to fit those goals and abilities. A game uses all these elements to sculpt a form of activity. And when we play games, we take on an alternate form of agency. ... Goals, abilities, and environment: these are the means by which game designers practice their art. And we experience the game designer's art by flexing our agency to fit.11

When we play games, we adopt a mode of agency by taking on the goals of the game for a limited time and adopting a particular agential mindset—"the pairings of a particular kind of interest with a focus on a particular set of skills". In other words, it teaches us, not some specific competencies, but what it is to be the kind of agent who takes a particular kind of action.

To give an example, when I was growing up, I played a lot of two-hand card games with my Dad: cribbage, piquet, gin rummy, whist. These gave me my first taste of what it is like to be in a negotiation.

In two-hand card games, each person has a set of options for what they can play, and they have some knowledge of what the other will play, based on the cards in the deck. One person may simply have a better hand and will be sure to win overall, but through deftly navigating what cards to play, and when, you can eke out more or less of the final pot.

These are some of the fundamental qualities of a negotiation. When I was first exposed to real negotiations in a business setting, I recognised the flavour of it from the card games that I used to play. There was no actual skill development to prepare me for negotiation. For each particular kind of negotiation I still had to learn everything about the options that were available to both parties, the way to communicate, and more, but the role of a negotiator was not new to me.

Nguyen writes about games in general, and my experience came from card games, but the principle is exactly the same in video games. RPGs help one to understand the role of uncovering more of the world and sculpting an identity, first-person shooters give a sense of the role of rapid decision-making, team coordination and fast twitch responses, and so on. These are not specific skills that can be used in the real world, but they are ways of thinking and being that prepare you for interacting with a real-world domain.

Tobi Lütke summarizes this principle when explaining why he encourages the use of video games at Shopify12:

It's just bound to be good for Shopify if people play Factorio. ... part of Shopify is building warehouses and fulfilling products for our customers. … Factorio makes a game out of that kind of thinking.

What are other situations where you can – in a compressed way – practice these skills that you need in the business world? I make strategic decisions for my job at the company. … How often do I do this in a year? A couple times, maybe once a month? I don’t think so. Major opportunities to bet the company and allocate resources don’t come around that often.

But if I sit down for an evening of poker, I make these decisions every hand. And then you look at a game like StarCraft … or Factorio, and in a very compressed, fun environment, follow a certain activity over and over and over again. And doing that will change your mind, and your brain, and help you be prepared for situations you could never predict ahead of time.

Understanding these different roles through video games is a profound gift. Video games allow for creative explorations of agency in many more dimensions than traditional games, and by having access to these other dimensions, we expand our understanding of the roles we can play. This is most helpful for young people and kids who otherwise would not have the opportunity to inhabit these kinds of agencies because of age, physicality, experience, etc.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that "Games offer easier entry points into novel modes of agency precisely because they are thinner, narrower, and more precisely defined". These agencies are not commensurate with the kinds of complicated and nuanced lives that we need, or want, to live every day. The reward that comes from the competence satisfaction of games, alongside the easy, simplified world that they present, means that video games are highly addictive.

Gaming disorder has been added to the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases, and it may enter the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the canonical reference book for psychological disorders in the US. Under the WHO’s definition, gaming disorder happens whenever there is a pattern of gaming behaviour that is uncontrollable and harms the rest of a life.

And many lives are being harmed—according to one 2021 metastudy, gaming disorder affects 2–3 percent of all gamers (similar to the number of problem gamblers among people who occasionally gamble). If this is true globally today, then there are 140 million people suffering from a video game addiction.

This is a big number, but it doesn’t diminish the good that video games do for our agency. Video games can help us develop new ways of approaching the world when we are just starting out on something, and that is exactly what we do as kids. The psychologist Jean Piaget saw play as a kind of assimilation, allowing a child to interpret environmental stimuli and incorporate them into their existing schema. When you are just starting out, you need access to simplified worlds in order to do this kind of play effectively, and video games offer more worlds like this then any other medium we have.

Video games allow us to adopt new roles and expand our agency and, at least at the beginning, can be a useful tool for learning a new skill. At some point, we need to grow up and put our games behind us; they will not help us become who we need to be13. But removing them altogether would make it impossible to use them effectively as part of growing up in the first place.

Conclusion

Video games have opened an entirely new dimension for human creativity and exploration, including new tactics for motivating activity and engaging in creative play. The newest kinds of Virtual Reality and the use of LLMs will likely allow this to go even further in creating spaces for novel play that can mimic many more aspects of the real world.

This play in video game environments leads to both a more adaptable and effective understanding of agency, as well as a limited set of real-skill acquisition related to these enclosed worlds.

However, play is not the real world. By their nature, games must select and constrain the kind of actions that players choose to take, reducing the complexity and dimensionality of the real world down to a particular basket of options to be selected from. This means there are fundamental limits to the training that can take place in a video game environment. It also means that video games risk creating some of the worst kinds of addiction. Like gambling, they give the user the illusion of a completely defined and controllable universe—a place where you never have to deal with the truly unknown.

We should not fear video games. Many things are by nature addictive but have come to be important parts of building our societies. Video games are genuinely useful in certain constrained environments and can offer us a path to adopting new stances as free agents. We just need to know where their boundaries lie.

Takeaways

Video games are a massive and growing industry. We need to understand the relationship between gaming and the development of competence.

At present, it seems like video games can help create rapid improve in very well-defined areas of practice but cannot be a replacement for real-world training. They should be used aggressively when starting on a learning curve but removed as soon as they become a hindrance.

More counter-intuitively, Video games can also teach us what it is like to be a particular kind of person and to operate with certain kinds of action. A way to prepare for roles we might take on in the world. Especially for children this is an essential part of development.

Video game addiction is real and harmful. We need to take it seriously.

Oddly, restrictions to decrease video game access by young people then make them fully available to adults are the opposite of an ideal scenario. It is children, who are still figuring out how to navigate the world and need more constrained play, who have the most to benefit from video games.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Robert Bellafiore and Case for reading early versions and providing essential feedback.

I couldn't have written this essay without the MIT Handbook of Game-Based Learning as a reference material for understanding the current research on video games and skill acquisition. C. Thi. Nguyen's book Games: Agency As Art was also essential. It is a wonderful piece of modern philosophy and a very inspiring work.

Footnotes

China is the largest video game market in the world and is home to some of the world's largest gaming companies, including the industry-leading Tencent. Following this news report, Tencent stock lost ~10 percent of its value in early trading (~$60 billion in value at the time), and the fall continued until the original article was taken down. The article later reappeared with the description of "spiritual opium" removed, and the stock ended down ~6 percent. Source.

Throughout this essay I am talking only about video games, not games in general or simulators. Though some of the points that apply to all games that are relevant when thinking about video games as pointed out. Simulators are an entirely other field and worth a deep dive themselves.

Ibid.

Ibid.

As in the case of Jann Mardenborough.

Games: Agency As Art

This series is about how we become competent so I’ve focussed here on this aspect of video games above all others. Though to be clear, there are many more reasons to use video games than simply to gain skills or see the world in new ways. They can also just be fun.

I think young men choose to game because of the lack of agency they feel in their youth, which I believe is attributable to the current public education model.

For too many young men the rigid K-12 system elminates possibilities of what they could become and can do.

Gaming fills the lack of adventure gap early on, only to further limit what children can do later on as an adult when they have dimished social, business, and trade skills.